Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The View From 30,000ft

- 3. Compiling Python Source Code

- 4. Python Objects

- 5. Code Objects

- 6. Frame Objects

- 7. Interpreter and Thread States

-

8. Intermezzo: The

abstract.cModule -

9. The evaluation loop,

ceval.c - 10. The Block Stack

- 11. From Class code to bytecode

- 12. Generators: Behind the scenes.

- Notes

1. Introduction

The Python Programming language has been around for a long time. Guido van Rossum started development work on the first version in 1989, and it has since grown to become one of the more popular languages used in a wide range of applications from graphical interfaces to finance and data analysis.

This write-up looks at the nuts and bolts of the Python interpreter. It targets CPython, the most popular, and reference implementation of Python at the point of this write-up.

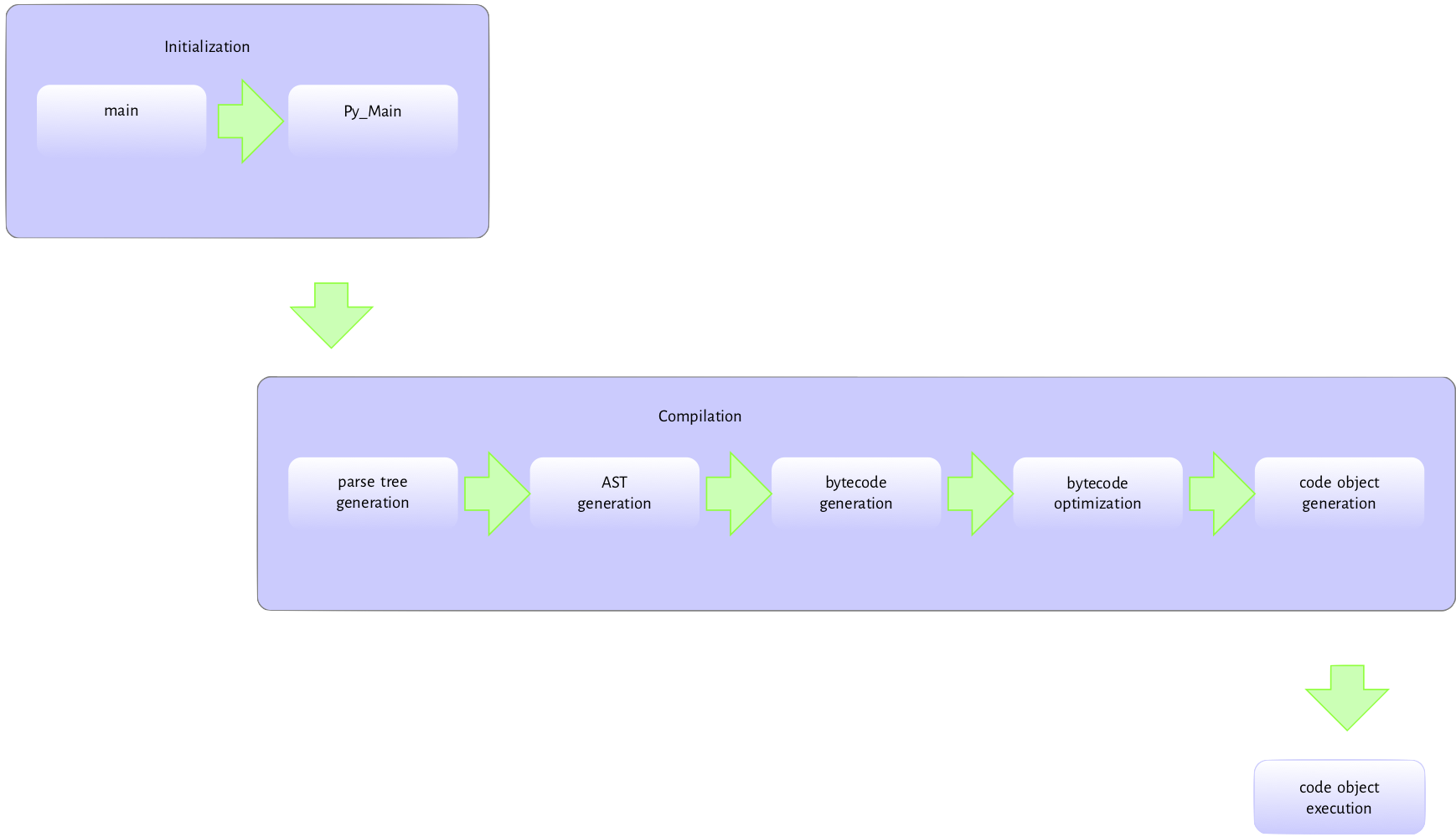

I regard the execution of a Python program as split into two or three main phases, as listed below. The relevant stages depend on how the interpreter is invoked, and this write-up covers them in different measures:

- Initialization: This step covers the set up of the various data structures needed by the Python process and is only relevant when a program is executed non-interactively through the command prompt.

- Compiling: This involves activities such as building syntax trees from source code, creating the abstract syntax tree, building the symbol tables, generating code objects etc.

- Interpreting: This involves the execution of the generated code object’s bytecode within some context.

The methods used in generating parse trees and syntax trees from source code are language-agnostic, so we do not spend much time on these. On the other hand, building symbol tables and code objects from the Abstract Syntax tree is the more exciting part of the compilation phase. This step is more Python-centric, and we pay particular attention to it. Topics we will cover include generating symbol tables, Python objects, frame objects, code objects, function objects etc. We will also look at how code objects are interpreted and the data structures that support this process.

This material is for anyone interested in gaining insight into how the CPython interpreter functions. The assumption is that the reader is already familiar with Python and understands the fundamentals of the language. As part of this exposition, we go through a

considerable amount of C code, so a reader with a rudimentary understanding of C will find it easier to follow. All that is needed to get through this material is a healthy desire to learn about the CPython virtual machine.

This work is an expanded version of personal notes taken while investigating the inner working of the Python interpreter. There is a substantial amount of wisdom in videos available in Pycon videos, school lectures and blog write-ups. This work will be incomplete without acknowledging these fantastic sources.

At the end of this write-up, a reader should understand the processes and data structures that are crucial to the execution of a Python program. We start next with an

overview of the execution of a script passed as a command-line argument to the interpreter. Readers can install the CPython executable from the source by following the instructions at the Python Developer’s Guide.

2. The View From 30,000ft

This chapter is a high-level overview of the processes involved in executing a Python program. Regardless of the complexity of a Python program, the techniques described here are the same. In subsequent chapters, we zoom in to give details on the various pieces of the puzzle. The excellent explanation of this process provided by Yaniv Aknin in his Python Internal series provides some of the basis and motivation for this discussion.

A method of executing a Python script is to pass it as an argument to the Python interpreter as such $python test.py. There are other ways of interacting with the interpreter

- we could start the interactive interpreter, execute a string as code, etc. However, these methods are not of interest to us.

Figure 2.1 is

the flow of activities involved in executing a module passed to the interpreter at the command-line.

The Python executable

is a C program like any other C program such as the Linux kernel or a simple hello world

program in C so pretty much the same process happens when we run the Python interpreter executable.

The executable’s entry point is the main method in the Programs/python.c. This main method handles basic initialization, such as memory allocation, locale setting, etc. Then, it invokes the Py_Main function in Modules/main.c responsible for the python specific initializations. These include parsing command-line arguments and setting program

flags, reading environment variables, running hooks, carrying out hash randomization, etc. After, Py_Main calls the Py_Initialize function in Programs/pylifecycle.c; Py_Initialize is responsible for initializing the interpreter and all associated objects and data structures required by the Python runtime. After Py_Initialize completes successfully, we now have access to all Python objects.

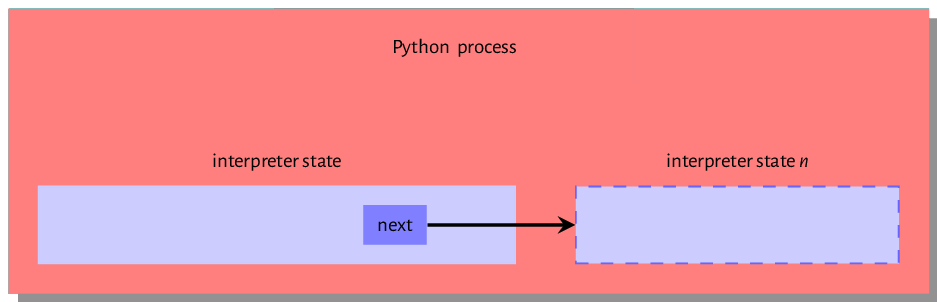

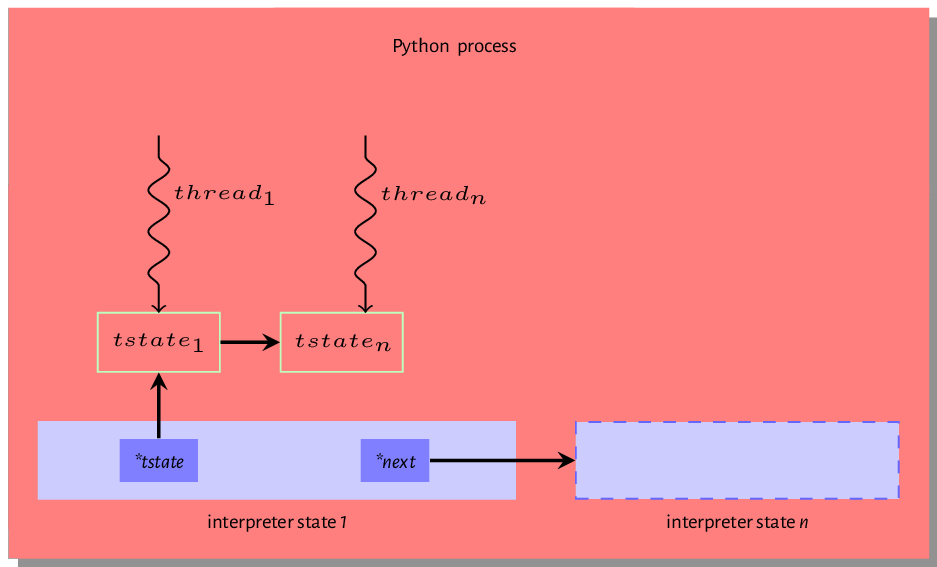

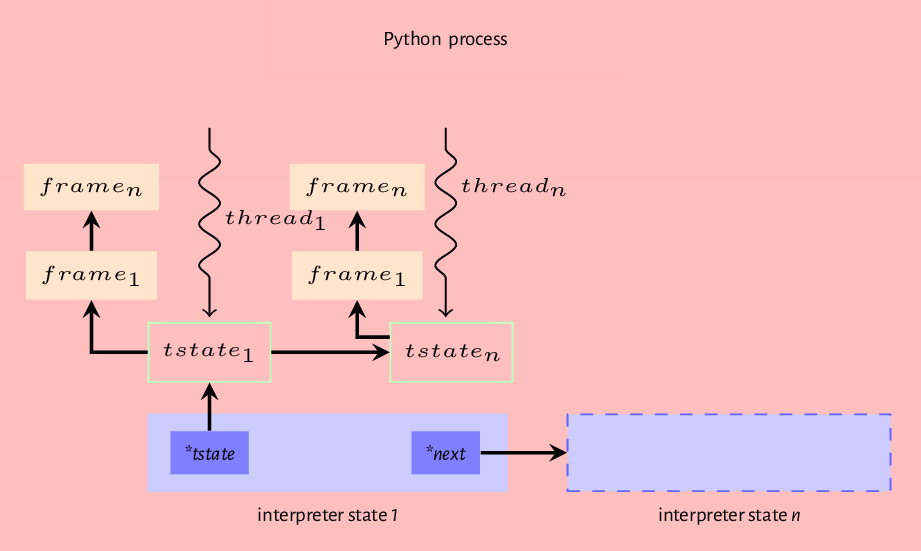

The interpreter state and interpreter state data structures are two examples of data structures that are initialized by the Py_Initialize call.

A look at the data structure definitions for these provides some context into their functions. The interpreter and thread states are C structures with pointers to fields that hold information needed for executing a program. Listing 2.1 is the interpreter state typedef (just assume that

typedef is C jargon for a type definition though this is not entirely true).

1 typedef struct _is {

2

3 struct _is *next;

4 struct _ts *tstate_head;

5

6 PyObject *modules;

7 PyObject *modules_by_index;

8 PyObject *sysdict;

9 PyObject *builtins;

10 PyObject *importlib;

11

12 PyObject *codec_search_path;

13 PyObject *codec_search_cache;

14 PyObject *codec_error_registry;

15 int codecs_initialized;

16 int fscodec_initialized;

17

18 PyObject *builtins_copy;

19 } PyInterpreterState;

Anyone who has used the Python programming language long enough may recognize a few of the fields mentioned in this structure (sysdict, builtins, codec)*.

- The

*nextfield is a reference to another interpreter instance as multiple python interpreters can exist within the same process. - The

*tstate_headfield points to the main thread of execution - if the Python program is multithreaded, then the interpreter is shared by all threads created by the program - we discuss the structure of a thread state shortly. - The

modules,modules_by_index,sysdict,builtins, andimportlibare self-explanatory - they are all defined as instances ofPyObjectwhich is the root type of all Python objects in the virtual machine world. We provide more details about Python objects in the chapters that will follow. - The

codec*related fields hold information that helps with the location and loading of encodings. These are very important for decoding bytes.

A Python program must execute in a thread. The thread state structure contains all the information needed by a thread to run some code. Listing 2.2 is a fragment of the thread data structure.

1 typedef struct _ts {

2 struct _ts *prev;

3 struct _ts *next;

4 PyInterpreterState *interp;

5

6 struct _frame *frame;

7 int recursion_depth;

8 char overflowed;

9

10 char recursion_critical;

11 int tracing;

12 int use_tracing;

13

14 Py_tracefunc c_profilefunc;

15 Py_tracefunc c_tracefunc;

16 PyObject *c_profileobj;

17 PyObject *c_traceobj;

18

19 PyObject *curexc_type;

20 PyObject *curexc_value;

21 PyObject *curexc_traceback;

22

23 PyObject *exc_type;

24 PyObject *exc_value;

25 PyObject *exc_traceback;

26

27 PyObject *dict; /* Stores per-thread state */

28 int gilstate_counter;

29

30 ...

31 } PyThreadState;

More details on the interpreter and the thread state data structures will follow in subsequent chapters. The initialization process also sets up the import mechanisms as well as rudimentary stdio.

After the initialization, the Py_Main function invokes the run_file function also in the main.c module. The following series of function calls:

PyRun_AnyFileExFlags -> PyRun_SimpleFileExFlags->PyRun_FileExFlags->PyParser_ASTFromFileObject

are made to the PyParser_ASTFromFileObject function.

The PyRun_SimpleFileExFlags function call creates the __main__ namespace in which the

file contents will be executed. It also checks for the presence of a pyc version of the module -

the pyc file contains the compiled version of the executing module. If a pyc version exists, it will attempt to read and execute it. Otherwise, the interpreter invokes thePyRun_FileExFlags function followed by a call to

the PyParser_ASTFromFileObject function and then the

PyParser_ParseFileObject function. The PyParser_ParseFileObject function reads the module content and builds a parse tree from it. The PyParser_ASTFromNodeObject function is then called with the parse tree as an argument and creates an abstract syntax tree (AST) from the parse tree.

The AST generated is then passed to the run_mod function. This function invokes the PyAST_CompileObject function that creates code objects from the AST. Do note that the bytecode generated during the call to PyAST_CompileObject

is passed through a simple peephole optimizer that carries out low hanging optimization of the generated bytecode

before creating the code object.

With the code objects created, it is time to execute the instructions encapsulated by the code objects.

The run_mod function invokes PyEval_EvalCode from the ceval.c file with

the code object as an argument. This results in another series of function calls:

PyEval_EvalCode->PyEval_EvalCode->_PyEval_EvalCodeWithName->_PyEval_EvalFrameEx. The code object is an argument to most of these functions.

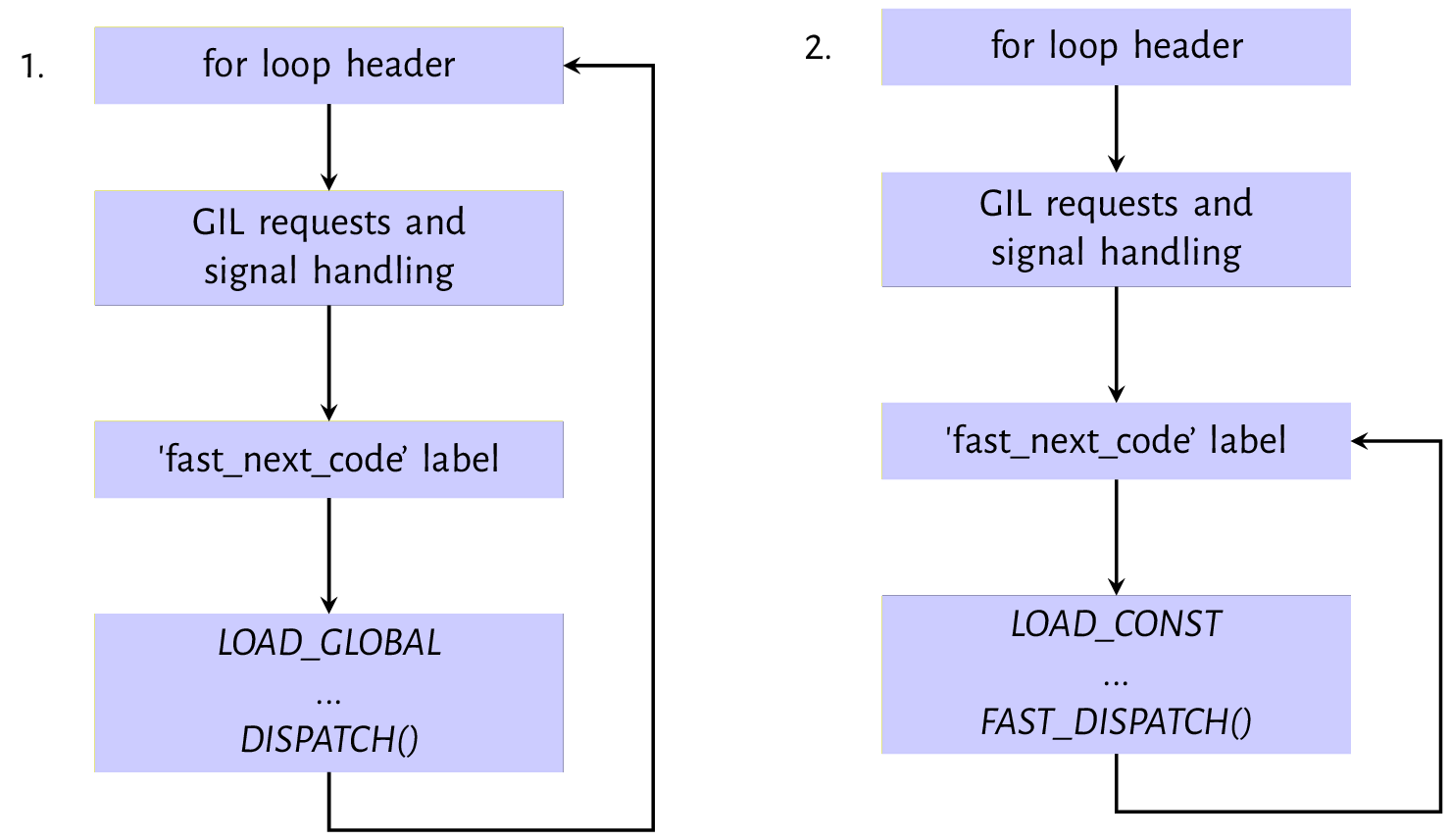

The _PyEval_EvalFrameEx is the actual execution loop that handles executing the code objects. This function gets called with a frame object as an argument. This frame object provides the context for executing the code object. The execution loop reads and executes instructions from an array of instructions, adding or removing objects from the value stack in the process (where is this value stack?), till there are no more instructions to execute or something exceptional that breaks this loop occurs.

Python provides a set of functions that one can use to explore actual code objects. For example, a a simple program can be compiled into a code object and disassembled to get the opcodes that are executed by the Python virtual machine, as shown in listing 2.3.

1 >>> from dis import dis

2 >>> def square(x):

3 ... return x*x

4 ...

5

6 >>> dis(square)

7 2 0 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

8 2 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

9 4 BINARY_MULTIPLY

10 6 RETURN_VALUE

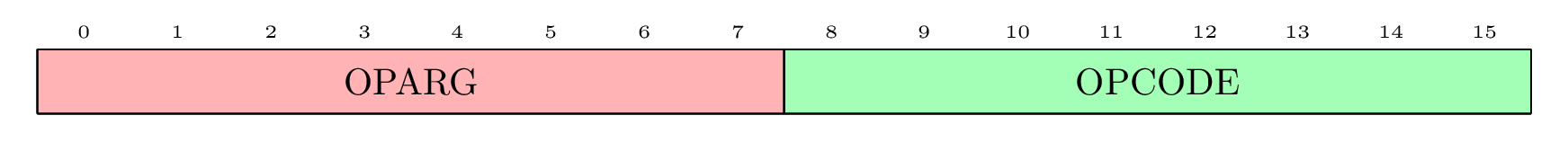

The ./Include/opcodes.h file contains a listing of the Python Virtual Machine’s bytecode instructions. The opcodes are pretty straight forward conceptually. Take our example from listing 2.3 with four

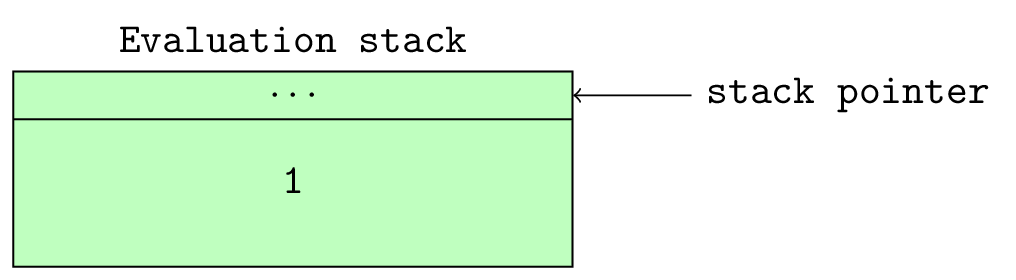

instructions - the LOAD_FAST opcode loads the value of its argument (x in this case) onto an evaluation (value) stack. The Python virtual machine is a

stack-based virtual machine, so values for operations and results from operations live on a stack.

The BINARY_MULTIPLY opcode then pops two items from the value stack, performs binary multiplication on both values, and places the result back on the value stack. The RETURN VALUE opcode pops a

value from the stack, sets the return value object to this value, and breaks out of the interpreter loop.

From the disassembly in listing 2.3, it is pretty clear that this rather simplistic explanation of the operation of the interpreter loop leaves out a lot of details. A few of these outstanding questions may include.

After the module’s execution, the Py_Main function continues with the clean-up process. Just as

Py_Initialize performs initialization during the interpreter startup, Py_FinalizeEx

is invoked to do some clean-up work; this clean-up process involves waiting for threads to exit, calling

any exit hooks, freeing up any memory allocated by the interpreter that is still in use, and so on, paving the way for the interpreter to exit.

The above is a high-level overview of the processes involved in executing a Python module. A lot of details are left out at this stage, but all will be revealed in subsequent chapters. We continue in the next chapter with a description of the compilation process.

3. Compiling Python Source Code

Although most people may not regard Python as a compiled language, it is one. During compilation, the interpreter generates executable bytecode from Python source code. However, Python’s compilation process is a relatively simple one. It involves the following steps in order.

- Parsing the source code into a parse tree.

- Transforming the parse tree into an abstract syntax tree (AST).

- Generating the symbol table.

- Generating the code object from the AST. This step involves:

- Transforming the AST into a flow control graph, and

- Emitting a code object from the control flow graph.

Parsing source code into a parse tree and creating an AST from such a parse is a standard process and Python does not introduce any complicated nuances, so the focus of this chapter is on the transformation of an AST into a control flow graph and the emission of code object from the control flow graph. For anyone interested in parse tree and AST generation, the dragon book provides an in-depth tour de force of both topics.

3.1 From Source To Parse Tree

The Python parser is an LL(1) parser based on the

description of such parsers laid out in the Dragon book. The Grammar/Grammar module contains the

Extended Backus-Naur Form (EBNF) grammar specification of the Python language. Listing 3.0 is a cross-section of this grammar.

1 stmt: simple_stmt | compound_stmt

2 simple_stmt: small_stmt (';' small_stmt)* [';'] NEWLINE

3 small_stmt: (expr_stmt | del_stmt | pass_stmt | flow_stmt |

4 import_stmt | global_stmt | nonlocal_stmt | assert_stmt)

5 expr_stmt: testlist_star_expr (augassign (yield_expr|testlist) |

6 ('=' (yield_expr|testlist_star_expr))*)

7 testlist_star_expr: (test|star_expr) (',' (test|star_expr))* [',']

8 augassign: ('+=' | '-=' | '*=' | '@=' | '/=' | '%=' | '&=' | '|=' | '^='

9 | '<<=' | '>>=' | '**=' | '//=')

10

11 del_stmt: 'del' exprlist

12 pass_stmt: 'pass'

13 flow_stmt: break_stmt | continue_stmt | return_stmt | raise_stmt |

14 yield_stmt

15 break_stmt: 'break'

16 continue_stmt: 'continue'

17 return_stmt: 'return' [testlist]

18 yield_stmt: yield_expr

19 raise_stmt: 'raise' [test ['from' test]]

20 import_stmt: import_name | import_from

21 import_name: 'import' dotted_as_names

22 import_from: ('from' (('.' | '...')* dotted_name | ('.' | '...')+)

23 'import' ('*' | '(' import_as_names ')' | import_as_names))

24 import_as_name: NAME ['as' NAME]

25 dotted_as_name: dotted_name ['as' NAME]

26 import_as_names: import_as_name (',' import_as_name)* [',']

27 dotted_as_names: dotted_as_name (',' dotted_as_name)*

28 dotted_name: NAME ('.' NAME)*

29 global_stmt: 'global' NAME (',' NAME)*

30 nonlocal_stmt: 'nonlocal' NAME (',' NAME)*

31 assert_stmt: 'assert' test [',' test]

32

33 ...

The PyParser_ParseFileObject function in Parser/parsetok.c is the entry point for parsing any module passed to the interpreter at the command-line. This function invokes the PyTokenizer_FromFile function that is responsible for generating tokens from the supplied modules.

3.2 Python tokens

Python source code consists of tokens. For example, return is a keyword token; 2 is a literal numeric token. Tokenization, the splitting of source code into constituent tokens, is the first task during parsing. The tokens from this step fall into the following categories.

- identifiers: These are names defined by a programmer. They include function names, variable names, class names, etc. These must conform to the rules of identifiers specified in the Python documentation.

- operators: These are special symbols such as

+,*that operate on data values, and produce results. - delimiters: This group of symbols serve to group expressions,

provide punctuations, and assignment. Examples in this category include

(, ),{,},=,*=etc. - literals: These are symbols that provide a constant value for some type. We have the string and

byte literals such as

"Fred",b"Fred"and numeric literals which include integer literals such as2, floating-point literal such as1e100and imaginary literals such as10j. - comments: These are string literals that start with the hash symbol. Comment tokens always end at the end of the physical line.

- NEWLINE: This is a unique token that denotes the end of a logical line.

- INDENT and DEDENT: These token represent indentation levels that group compound statements.

A group of tokens delineated by the NEWLINE token makes up a logical line; hence we could say that a Python program consists of a sequence of logical lines. Each of these logical lines consists of several physical lines that are each terminated by an end-of-line sequence. Most times, logical lines map to physical lines, so we have a logical line delimited by end-of-line characters. These logical lines usually map to Python statements. Compound statements may span multiple physical lines; parenthesis, square brackets or curly braces around a statement implicitly joins the logical lines that make up such statement. The backslash character, on the other hand, is needed to join multiple logical lines explicitly.

Indentation also plays a central role in grouping Python statements. One of the lines in the Python grammar is thus suite: simple_stmt | NEWLINE INDENT stmt+ DEDENT so a crucial task of the tokenizer generating indent and dedent tokens that go into the parse tree. The tokenizer uses an algorithm similar to that in Listing 3.1 to generate these INDENT and DEDENT tokens.

1 Init the indent stack with the value 0.

2 For each logical line taking into consideration line-joining:

3 A. If the current line's indentation is greater than the

4 indentation at the top of the stack

5 1. Add the current line's indentation to the top of the stack.

6 2. Generate an INDENT token.

7 B. If the current line's indentation is less than the indentation

8 at the top of the stack

9 1. If there is no indentation level on the stack that matches the current li\

10 ne's indentation, report an error.

11 2. For each value at the top of the stack, that is unequal to the current l\

12 ine's indentation.

13 a. Remove the value from the top of the stack.

14 b. Generate a DEDENT token.

15 C. Tokenize the current line.

16 For every indentation on the stack except 0, produce a DEDENT token.

The PyTokenizer_FromFile function in the Parser/tokenizer.c scans the source file from left to right and top to bottom tokenizing the file’s contents and then outputting a tokenizer structure. Whitespaces characters other

than terminators serve to delimit tokens but are not compulsory. In cases of ambiguity such as in 2+2, a token comprises the longest possible string that forms a legal token reading from left to right; in this example, the tokens are the literal 2, the operator + and the literal 2.

The tokenizer structure generated by the PyTokenizer_FromFile function gets passed to the parsetok function

that attempts to build a parse tree according to the Python grammar of which Listing 3.0 is a subset. When the parser encounters a token that violates the Python grammar, it raises a SyntaxError exception. The parser module provides limited access to the parse tree of a block of Python code, and listing 3.2 is a basic demonstration.

1 >>>code_str = """def hello_world():

2 return 'hello world'

3 """

4 >>> import parser

5 >>> from pprint import pprint

6 >>> st = parser.suite(code_str)

7 >>> pprint(parser.st2list(st))

8 [257,

9 [269,

10 [294,

11 [263,

12 [1, 'def'],

13 [1, 'hello_world'],

14 [264, [7, '('], [8, ')']],

15 [11, ':'],

16 [303,

17 [4, ''],

18 [5, ''],

19 [269,

20 [270,

21 [271,

22 [277,

23 [280,

24 [1, 'return'],

25 [330,

26 [304,

27 [308,

28 [309,

29 [310,

30 [311,

31 [314,

32 [315,

33 [316,

34 [317,

35 [318,

36 [319,

37 [320,

38 [321,

39 [322, [323, [3, '"hello world"']]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]],

40 [4, '']]],

41 [6, '']]]]],

42 [4, ''],

43 [0, '']]

44 >>>

The parser.suite(source) call in listing 3.2 returns an intermediate representation of a parse tree (ST) object while the call to parser.st2list returns the parse tree represented by a Python list - each list represents a node of the parse tree. The first items in each list, the integer, identifies the production rule in the Python grammar responsible for that node.

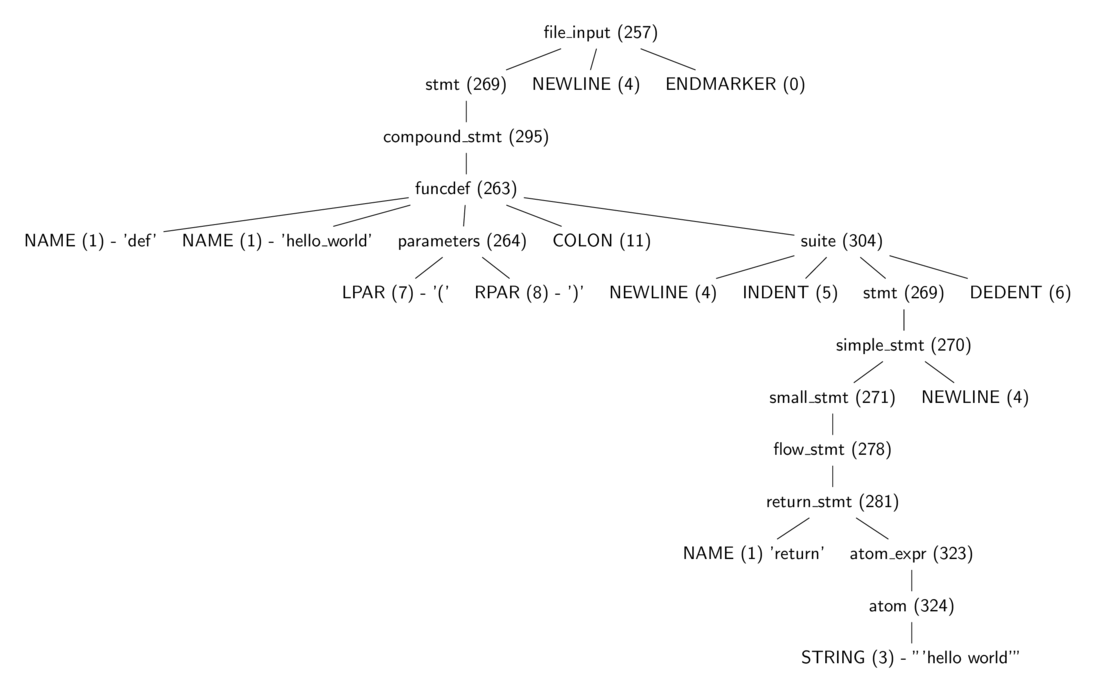

Figure 3.0 is a tree diagram of the same parse tree from listing 3.2 with some tokens stripped away, and one can see more easily the part of the grammar each of the integer value represents. These production

rules are all specified in the Include/token.h (terminals) and Include/graminit.h (terminals)

header files.

3.3 From Parse Tree To Abstract Syntax Tree

The parse tree is dense with information about Python’s syntax, and all that information such as how lines are delimited is irrelevant for generating bytecode. This is where the abstract syntax tree (AST) comes in. The abstract syntax tree is a representation of the code that is independent of Python’s syntax niceties. For example, a parse tree contains syntax constructs such as colon and NEWLINE nodes, as shown in figure 3.0, but the AST does not include such syntax construct as shown in listing 3.4. The transformation of the parse tree to the abstract syntax tree is the next step in the compilation pipeline.

ast module to manipulate the AST of python source code 1 >>> import ast

2 >>> import pprint

3 >>> node = ast.parse(code_str, mode="exec")

4 >>> ast.dump(node)

5 ("Module(body=[FunctionDef(name='hello_world', args=arguments(args=[], "

6 'vararg=None, kwonlyargs=[], kw_defaults=[], kwarg=None, defaults=[]), '

7 "body=[Return(value=Str(s='hello world'))], decorator_list=[], "

8 'returns=None)])')

Python makes use of the Zephyr Abstract Syntax Definition Language (ASDL), and the ASDL definitions of the various Python constructs are in the file Parser/Python.asdl file. Listing 3.5 is a fragment of the ASDL definition of a Python statement.

1 stmt = FunctionDef(identifier name, arguments args,

2 stmt* body, expr* decorator_list, expr? returns)

3 | AsyncFunctionDef(identifier name, arguments args,

4 stmt* body, expr* decorator_list, expr? returns)

5

6 | ClassDef(identifier name,

7 expr* bases,

8 keyword* keywords,

9 stmt* body,

10 expr* decorator_list)

11 | Return(expr? value)

12

13 | Delete(expr* targets)

14 | Assign(expr* targets, expr value)

15 | AugAssign(expr target, operator op, expr value)

16 -- 'simple' indicates that we annotate simple name without parens

17 | AnnAssign(expr target, expr annotation, expr? value, int simple)

18

19 -- use 'orelse' because else is a keyword in target languages

20 | For(expr target, expr iter, stmt* body, stmt* orelse)

21 | AsyncFor(expr target, expr iter, stmt* body, stmt* orelse)

22 | While(expr test, stmt* body, stmt* orelse)

23 | If(expr test, stmt* body, stmt* orelse)

24 | With(withitem* items, stmt* body)

25 | AsyncWith(withitem* items, stmt* body)

The PyAST_FromNode function in the Python/ast.c calls PyAST_FromNodeObject also in Python/ast.c which walks the various parse tree nodes and generates AST nodes accordingly using functions defined in Python/ast.c. The heart of this function is a large switch statement that calls node specific functions on each node type. For example, the code responsible for generating the AST node for an if expression is in listing 3.7.

1 static expr_ty

2 ast_for_ifexpr(struct compiling *c, const node *n)

3 {

4 /* test: or_test 'if' or_test 'else' test */

5 expr_ty expression, body, orelse;

6

7 assert(NCH(n) == 5);

8 body = ast_for_expr(c, CHILD(n, 0));

9 if (!body)

10 return NULL;

11 expression = ast_for_expr(c, CHILD(n, 2));

12 if (!expression)

13 return NULL;

14 orelse = ast_for_expr(c, CHILD(n, 4));

15 if (!orelse)

16 return NULL;

17 return IfExp(expression, body, orelse, LINENO(n), n->n_col_offset,

18 c->c_arena);

19 }

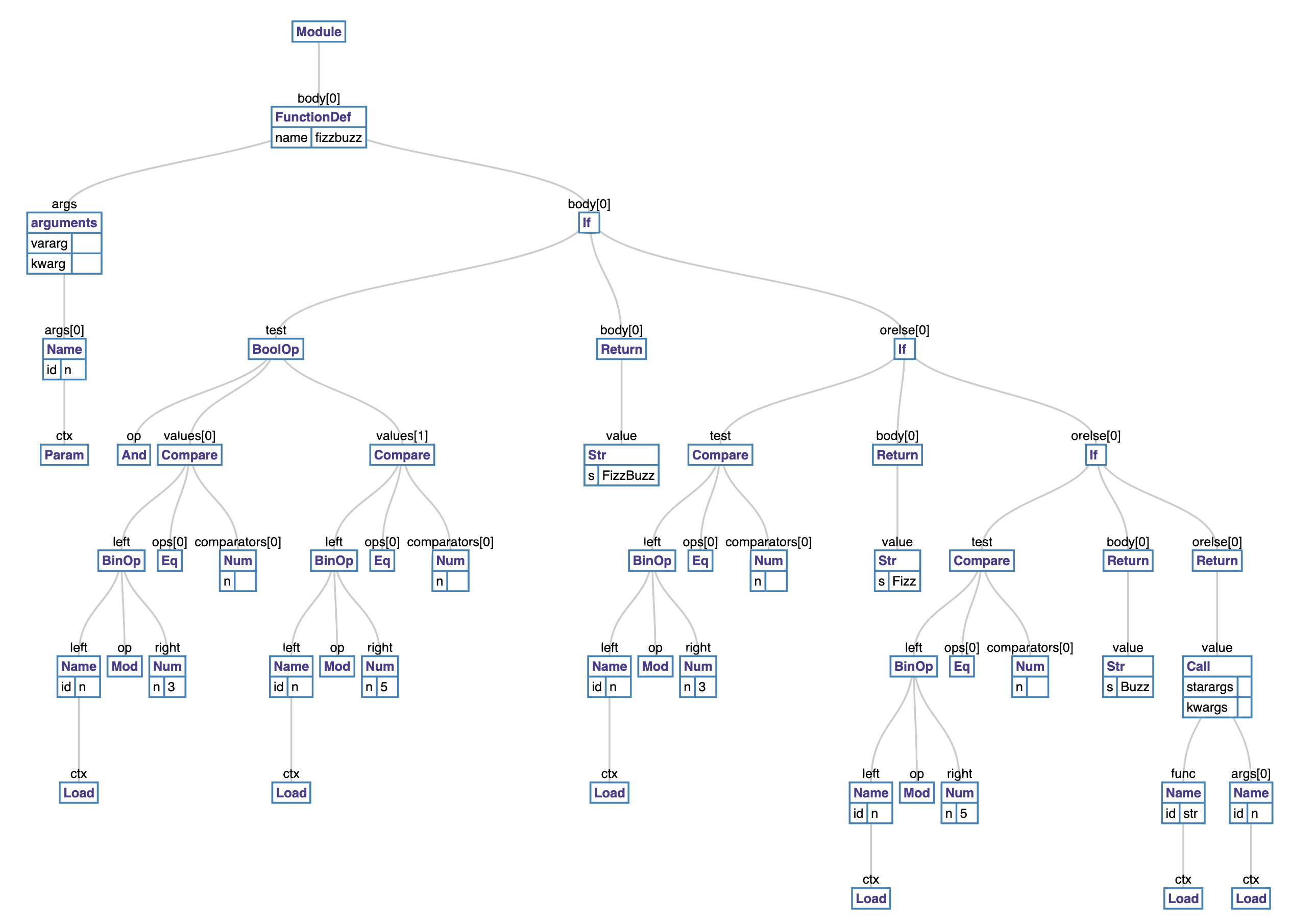

1 def fizzbuzz(n):

2 if n % 3 == 0 and n % 5 == 0:

3 return 'FizzBuzz'

4 elif n % 3 == 0:

5 return 'Fizz'

6 elif n % 5 == 0:

7 return 'Buzz'

8 else:

9 return str(n)

Take the code in Listing 3.8, for example, the transformation of its parse tree to an AST will result in an AST similar to figure 3.1.

The ast module bundled with the Python interpreter provides us with the ability to manipulate a Python AST. Tools such as codegen

can take an AST representation in Python and output the corresponding Python source code.

With the AST generated, the next step is creating the symbol table.

3.4 Building The Symbol Table

The symbol table, as the name suggests, is a collection of symbols and their use context within a code block. Building the symbol table involves analyzing and assigning scoping to the names in a code block.

The PySymtable_BuildObject function in Python/compile.c walks the AST to create the symbol table. This is a two-step process summarized in listing 3.12.

First, we visit each node of the AST to build a collection of symbols used. After the first pass, the symbol table entries contain all names that

have been used within the module, but it does not have contextual information about such names.

For example, the interpreter cannot tell if a given variable is a global, local, or free variable.

The symtable_analyze function in the Parser/symtable.c handles the second phase. In this phase, the algorithm assigns scopes (local, global, or free) to the symbols gathered from the first pass. The comments in the Parser/symtable.c are quite informative and are paraphrased below to provide some insight into the second phase of the symbol table construction process.

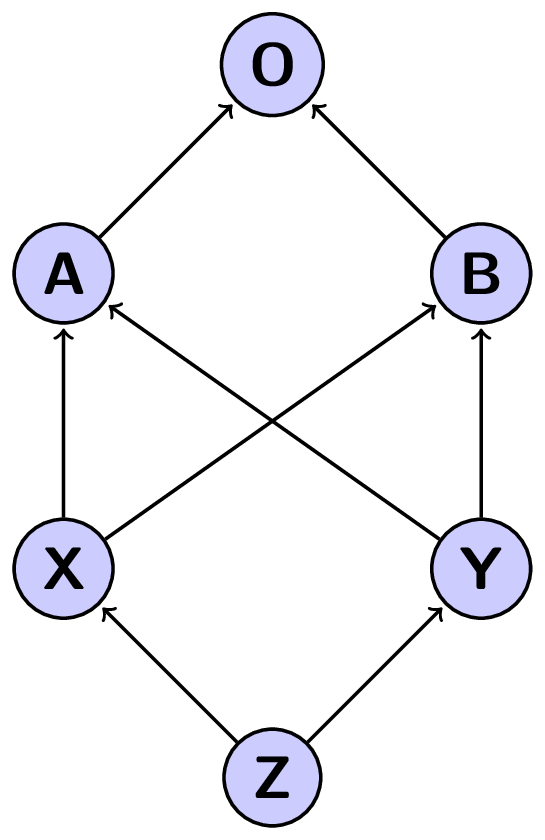

The symbol table requires two passes to determine the scope of each name. The first pass collects raw facts from the AST via the symtable_visit_* functions while the second pass analyzes these facts during a pass over the PySTEntryObjects created during pass 1. During the second pass, the parent passes the set of all name bindings visible to its children when it enters a function. These bindings determine if nonlocal variables are free or implicit globals. Names which are explicitly declared nonlocal must exist in this set of visible names - if they do not, the interpreter raises a syntax error. After the local analysis, it analyzes each of its child blocks using an updated set of name bindings.

There are also two kinds of global variables, implicit and explicit. An explicit global is declared with the global statement. An implicit global is a free variable for which the compiler has found no binding in an enclosing function scope. The implicit global is either a global or a builtin.

Python’s module and class blocks use thexxx_NAMEopcodes to handle these names to implement slightly odd semantics. In such a block, the name is treated as global until it is assigned a value; then it is treated like a local.The children update the free variable set. If a child adds a variable to the set of free variables, then such variable is marked as a cell. The function object defined must provide runtime storage for the variable that may outlive the function’s frame. Cell variables are removed from the free set before the analyze function returns to its parent.

For example, a symbol table for a module with content in listing 3.16 will contain three symbol table entries.

def make_counter():

count = 0

def counter():

nonlocal count

count += 1

return count

return counter

The first entry is that of the enclosing module, and it will have make_counter defined with a local scope. The next symbol

table entry will be that of function make_counter, and this will have the count and counter names marked as local. The final symbol table entry will be that of the nested counter function.

This entry will have the count variable marked as free. One thing to note is that although make_counter has a local scope in the symbol table entry for the module block, it is globally defined

in the module code block because the *st_global field of the symbol table points to the *st_top symbol table entry which is that of the enclosing module.

3.5 From AST To Code Objects

After generating the symbol table, the next step is creating code objects. The functions for this step are in the Python/compile.c module. First, they convert the AST into basic blocks of Python byte code

instructions. Basic blocks are blocks of code that have a single entry but can have multiple exits.

The algorithm here uses a pattern similar to that used to generate the symbol table. Functions named compiler_visit_xx, where xx is the node type, recursively visit each node of the AST emitting bytecode instructions in the process. We see some examples of these functions in the sections that follow.

The blocks of bytecode here implicitly represent a graph, the control flow graph.

This graph shows the potential code execution paths. In the second step, the algorithm flattens the control flow graph using a post-order depth-first search transversal. After, the jump offsets are calculated and used as instruction arguments for bytecode jump instructions. The bytecode instructions are then used to create a code object.

Basic blocks

The basic block is central to generating code objects. A basic block is a sequence of instructions that has one entry point but multiple exit points. Listing 3.19 is the definition of the basic_block data structure.

basicblock_ data strcuture 1 typedef struct basicblock_ {

2 /* Each basicblock in a compilation unit is linked via b_list in the

3 reverse order that the block are allocated. b_list points to the next

4 block, not to be confused with b_next, which is next by control flow. */

5 struct basicblock_ *b_list;

6 /* number of instructions used */

7 int b_iused;

8 /* length of instruction array (b_instr) */

9 int b_ialloc;

10 /* pointer to an array of instructions, initially NULL */

11 struct instr *b_instr;

12 /* If b_next is non-NULL, it is a pointer to the next

13 block reached by normal control flow. */

14 struct basicblock_ *b_next;

15 /* b_seen is used to perform a DFS of basicblocks. */

16 unsigned b_seen : 1;

17 /* b_return is true if a RETURN_VALUE opcode is inserted. */

18 unsigned b_return : 1;

19 /* depth of stack upon entry of block, computed by stackdepth() */

20 int b_startdepth;

21 /* instruction offset for block, computed by assemble_jump_offsets() */

22 int b_offset;

23 } basicblock;

The interesting fields here are *b_list that is a linked list of all basic blocks allocated during the compilation process, *b_instr which is an array of instructions within the basic block and *b_next which is the next basic flow reached by normal control flow execution. Each instruction has a structure shown in Listing 3.20 that holds a bytecode instruction. These bytecode instructions are in the Include/opcode.h header file.

instr data strcuture1 struct instr {

2 unsigned i_jabs : 1;

3 unsigned i_jrel : 1;

4 unsigned char i_opcode;

5 int i_oparg;

6 struct basicblock_ *i_target; /* target block (if jump instruction) */

7 int i_lineno;

8 };

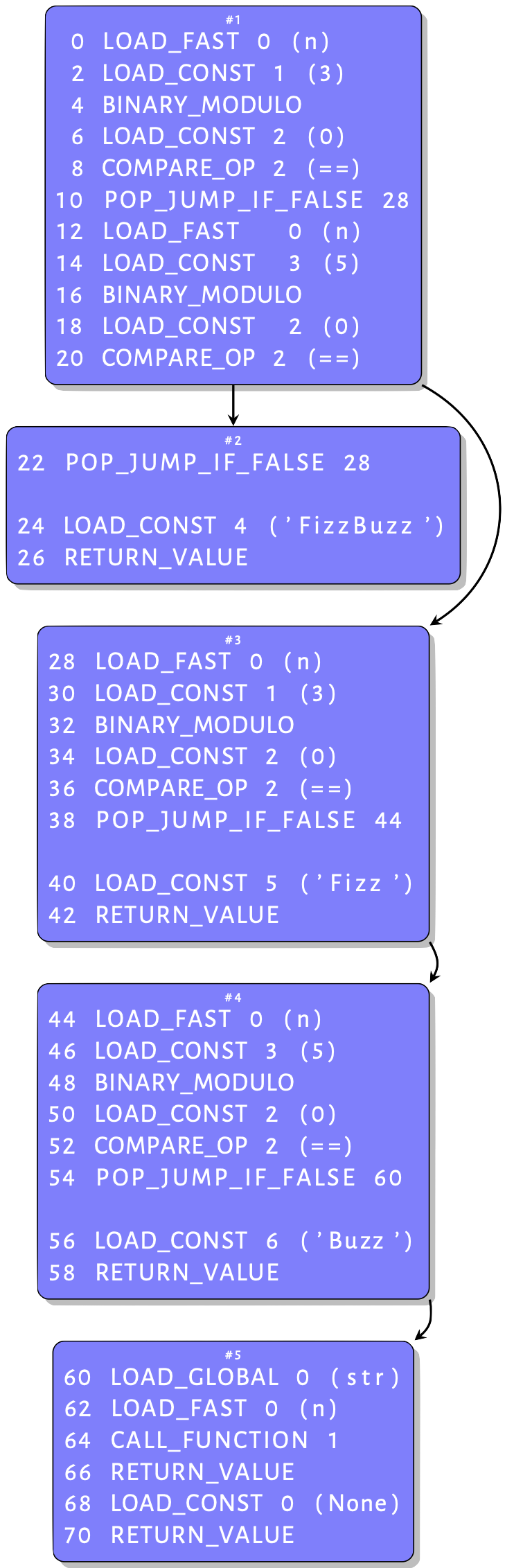

To illustrate how the interpreter creates these basic blocks, we use the function in Listing 3.11. Compiling its AST shown in figure 3.2 into a CFG results in the graph similar to that in figure 3.4 - this shows only blocks with instructions. An inspection of this graph provides some intuition behind the basic blocks. Some basic blocks have a single entry point, but others have multiple exits. These blocks are described in more detail next.

if statement 1 static int

2 compiler_if(struct compiler *c, stmt_ty s)

3 {

4 basicblock *end, *next;

5 int constant;

6 assert(s->kind == If_kind);

7 end = compiler_new_block(c);

8 if (end == NULL)

9 return 0;

10

11 constant = expr_constant(c, s->v.If.test);

12 /* constant = 0: "if 0"

13 * constant = 1: "if 1", "if 2", ...

14 * constant = -1: rest */

15 if (constant == 0) {

16 if (s->v.If.orelse)

17 VISIT_SEQ(c, stmt, s->v.If.orelse);

18 } else if (constant == 1) {

19 VISIT_SEQ(c, stmt, s->v.If.body);

20 } else {

21 if (asdl_seq_LEN(s->v.If.orelse)) {

22 next = compiler_new_block(c);

23 if (next == NULL)

24 return 0;

25 }

26 else

27 next = end;

28 VISIT(c, expr, s->v.If.test);

29 ADDOP_JABS(c, POP_JUMP_IF_FALSE, next);

30 VISIT_SEQ(c, stmt, s->v.If.body);

31 if (asdl_seq_LEN(s->v.If.orelse)) {

32 ADDOP_JREL(c, JUMP_FORWARD, end);

33 compiler_use_next_block(c, next);

34 VISIT_SEQ(c, stmt, s->v.If.orelse);

35 }

36 }

37 compiler_use_next_block(c, end);

38 return 1;

39 }

The body of the function in Listing 3.13 is an if statement as is visible in figure 3.2. The snippet in Listing 3.21 is the function that compiles an if statement AST node into basic blocks. When this function compiles our example if statement node, the else statement on line 20 is executed. First, it creates a new basic block for an else node if such exists. Then, it visits the guard clause of the if statement node. What we have in the function in Listing 3.11 is interesting because the guard clause is a boolean expression which can trigger a jump during execution. Listing 3.22 is the function that compiles a boolean expression.

1 static int compiler_boolop(struct compiler *c, expr_ty e)

2 {

3 basicblock *end;

4 int jumpi;

5 Py_ssize_t i, n;

6 asdl_seq *s;

7

8 assert(e->kind == BoolOp_kind);

9 if (e->v.BoolOp.op == And)

10 jumpi = JUMP_IF_FALSE_OR_POP;

11 else

12 jumpi = JUMP_IF_TRUE_OR_POP;

13 end = compiler_new_block(c);

14 if (end == NULL)

15 return 0;

16 s = e->v.BoolOp.values;

17 n = asdl_seq_LEN(s) - 1;

18 assert(n >= 0);

19 for (i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

20 VISIT(c, expr, (expr_ty)asdl_seq_GET(s, i));

21 ADDOP_JABS(c, jumpi, end);

22 }

23 VISIT(c, expr, (expr_ty)asdl_seq_GET(s, n));

24 compiler_use_next_block(c, end);

25 return 1;

26 }

The code up to the loop at line 20 is straight forward. In the loop, the compiler visits each expression, and after each visit, it adds a jump. This is because of the short circuit evaluation used by Python. It means that when a boolean operation such as an AND evaluates to false, the interpreter ignores the other expressions and performs a jump to continue execution. The compiler knows where to jump to if need be because the following instructions go into a new basic block - the use of compiler_use_next_block enforces this. So we have two blocks now. After visiting the test, the compiler_if function adds a jump instruction for the if statement, then compiles the body of the if statement. Recall that after visiting the boolean expression, the compiler created a new basic block. This block contains the jump and instructions for body of the if statement, a simple return in this case. The target of this jump is the next block that will hold the elif arm of the if statement. The next step is to compile the elif component of the if statement but before this, the compiler calls the compiler_use_next_block function to activate the next block. The orElse arm is just another if statement, so the compiler_if function gets called again. This time around the test of the if is a compare operation. This is a single comparison, so there are no jumps involved and no new blocks, so the interpreter emits byte code for comparing values and returns to compile the body of the if statement. The same process continues for the last orElse arm resulting in the CFG in figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3 shows that the fizzbuzz function can exit block 1 in two ways. The first is via serial execution of all the instructions in block 1 then continuing in block 2. The other is via the jump instruction after the first compare operation. The target of this jump is block 3, but an executing code object knows nothing of basic blocks – the code object has a stream of bytecodes that are indexed with offsets. We have to provide the jump instructions with the offset into the bytecode instruction stream of the jump targets.

Assembling the basic blocks

The assemble function in Python/compile.c linearizes the CFG and creates the code object from the linearized CFG. It does so by computing the instruction offset for jump targets and using these as arguments to the jump instructions.

First, the assemble function, in this case, adds instructions for a return None statement since the last statement of the function is not a RETURN statement - now you know why you can define methods without adding a RETURN

statement. Next, it flattens the CFG using a post-order depth-first traversal - the post-order traversal visits the children of a node before visiting the node itself. The assembler data structure holds the flattened graph, [block 5, block 4, block 3, block 2, block 1], in the a_postorder array for further processing. Next, it computes the instruction offsets and uses those as targets for the bytecode jump instructions. The assemble_jump_offsets function in listing 3.24 handles this.

The assemble_jump_offsets function in Listing 3.24 is relatively straightforward. In the for...loop at line 10, it computes the offset into the instruction stream for every instruction (akin to an array index). In the next for...loop at line 17, it uses the computed offsets as arguments to the jump instructions distinguishing between absolute and relative jumps.

1 static void assemble_jump_offsets(struct assembler *a, struct compiler *c){

2 basicblock *b;

3 int bsize, totsize, extended_arg_recompile;

4 int i;

5

6 /* Compute the size of each block and fixup jump args.

7 Replace block pointer with position in bytecode. */

8 do {

9 totsize = 0;

10 for (i = a->a_nblocks - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

11 b = a->a_postorder[i];

12 bsize = blocksize(b);

13 b->b_offset = totsize;

14 totsize += bsize;

15 }

16 extended_arg_recompile = 0;

17 for (b = c->u->u_blocks; b != NULL; b = b->b_list) {

18 bsize = b->b_offset;

19 for (i = 0; i < b->b_iused; i++) {

20 struct instr *instr = &b->b_instr[i];

21 int isize = instrsize(instr->i_oparg);

22 /* Relative jumps are computed relative to

23 the instruction pointer after fetching

24 the jump instruction.

25 */

26 bsize += isize;

27 if (instr->i_jabs || instr->i_jrel) {

28 instr->i_oparg = instr->i_target->b_offset;

29 if (instr->i_jrel) {

30 instr->i_oparg -= bsize;

31 }

32 instr->i_oparg *= sizeof(_Py_CODEUNIT);

33 if (instrsize(instr->i_oparg) != isize) {

34 extended_arg_recompile = 1;

35 }

36 }

37 }

38 }

39 } while (extended_arg_recompile);

40 }

With instructions offset calculated and jump offsets assembled, the compiler emits instructions contained in the flattened graph in reverse post-order from the traversal. The reverse post order is a topological sorting of the CFG. This means for every edge from vertex u to vertex v, u comes before v in the sorting order. This is obvious; we want a node that jumps to another node to always come before that jump target. After emitting the bytecode instructions, the compiler creates code objects for each code block using the emitted bytecode and information contained in the symbol table. The generated code object is returned to the calling function marking the end of the compilation process.

4. Python Objects

In this chapter, we look at the Python objects and their implementation in the CPython virtual machine. This is central to understanding the Python virtual machine’s internals. Most of the source referenced in this chapter is available in the Include/ and Objects/ directories. Unsurprisingly, the implementation of the Python object system is quite complex, so we try to avoid getting bogged down in the gory details of the C implementation. To kick this off, we start by looking at the PyObject structure - the workhorse of the Python object system.

4.1 PyObject

A cursory inspection of the CPython source code reveals the ubiquity of the PyObject structure. As we will see later on in this treatise, all the value stack objects used by the interpreter during evaluation are PyObjects.

For want of a better term, we refer to this as the superclass of all

Python objects. Values are never declared as PyObject but a pointer to any object can be cast to a PyObject. In layman’s term, any object can be treated as a PyObject structure because the initial

segment of all objects is a PyObject structure.

Listing 4.0 is a definition of the PyObject structure. This structure is composed of several fields that must be

filled for a value to be treated as an object.

1 typedef struct _object {

2 _PyObject_HEAD_EXTRA

3 Py_ssize_t ob_refcnt;

4 struct _typeobject *ob_type;

5 } PyObject;

The _PyObject_HEAD_EXTRA when present is a C macro that defines fields that point to the previously allocated

object and the next object, thus forming an implicit doubly-linked list of all live objects.

The ob_refcnt field is for memory management, while the *ob_type is a pointer to the type object for the given object. This type determines what the data represents, what kind of data it contains, and the kind of operations the object supports. Take the snippet in Listing 4.1 for example, the name, name, points to a string object, and the type of the object is “str”.

1 >>> name = 'obi'

2 >>> type(name)

3 <class 'str'>

A valid question from here is if the type field points to a type object then what does the *ob_type field of that type object point to? The ob_type for a type object recursively refers to itself hence the saying that the type of a type is type.

Types in the VM are implemented using the _typeobject data structure defined in the Objects/Object.h

module. This is a C struct with fields for mostly functions or collections of functions filled in by each type. We look at this data structure next.

4.2 Dissecting Types

The _typeobject structure defined in Include/Object.h serves as the base structure of all

Python types. The data structure defines a large number of fields that are mostly pointers to C functions

that implement some functionality for a given type. Listing 4.2 is the _typeobject structure definition.

1 typedef struct _typeobject {

2 PyObject_VAR_HEAD

3 const char *tp_name; /* For printing, in format "<module>.<name>" */

4 Py_ssize_t tp_basicsize, tp_itemsize; /* For allocation */

5

6 destructor tp_dealloc;

7 printfunc tp_print;

8 getattrfunc tp_getattr;

9 setattrfunc tp_setattr;

10 PyAsyncMethods *tp_as_asyn;

11

12 reprfunc tp_repr;

13

14 PyNumberMethods *tp_as_number;

15 PySequenceMethods *tp_as_sequence;

16 PyMappingMethods *tp_as_mapping;

17

18 hashfunc tp_hash;

19 ternaryfunc tp_call;

20 reprfunc tp_str;

21 getattrofunc tp_getattro;

22 setattrofunc tp_setattro;

23

24 PyBufferProcs *tp_as_buffer;

25 unsigned long tp_flags;

26 const char *tp_doc; /* Documentation string */

27

28 traverseproc tp_traverse;

29

30 inquiry tp_clear;

31 richcmpfunc tp_richcompare;

32 Py_ssize_t tp_weaklistoffset;

33

34 getiterfunc tp_iter;

35 iternextfunc tp_iternext;

36

37 struct PyMethodDef *tp_methods;

38 struct PyMemberDef *tp_members;

39 struct PyGetSetDef *tp_getset;

40 struct _typeobject *tp_base;

41 PyObject *tp_dict;

42 descrgetfunc tp_descr_get;

43 descrsetfunc tp_descr_set;

44 Py_ssize_t tp_dictoffset;

45 initproc tp_init;

46 allocfunc tp_alloc;

47 newfunc tp_new;

48 freefunc tp_free;

49 inquiry tp_is_gc;

50 PyObject *tp_bases;

51 PyObject *tp_mro;

52 PyObject *tp_cache;

53 PyObject *tp_subclasses;

54 PyObject *tp_weaklist;

55 destructor tp_del;

56

57 unsigned int tp_version_tag;

58 destructor tp_finalize;

59 } PyTypeObject;

The PyObject_VAR_HEAD field is an extension of the PyObject field discussed in the previous section; this extension adds an

ob_size field for objects that have the notion of length. The Python C API documentation contains a description of each of the fields in this object structure. The critical thing

to note is that the fields in the structure each implement a part of the type’s behavior. Most of these fields are part of what we can call an object interface or protocol; the types implement these functions but in a type-specific way.

For example, tp_hash field is a reference to a hash function for a given type - this

field could be left without a value in the case where instances of the type are not hashable;

whatever function is in the tp_hash field gets invoked when the hash method is called on an instance of that

type. The type object also has the field - tp_methods that references methods unique to that type.

The tp_new slot refers to a function that creates new instances of the type and so

on. Some of these fields, such as tp_init, are optional - not every type needs to run an initialization function, especially when the type is immutable, such as tuples. In contrast, other fields, such as tp_new, are compulsory.

Also, among these fields are fields for other Python protocols, such as the following.

- Number protocol - A type implementing this protocol will have implementations for the

PyNumberMethods *tp_as_numberfield. This field is a reference to a set of functions that implement arithmetic operations (this does not necessarily have to be on numbers). A type will support arithmetic operations with their corresponding implementations included in thetp_as_numberset in the type’s specific way. For example, the non-numericsettype has an entry into this field because it supports arithmetic operations such as-,<=, and so on. - Sequence protocol - A type that implements this protocol will have a value in the

PySequenceMethods *tp_as_sequencefield. This value should provide that type with support for some sequence operations such aslen,inetc. - Mapping protocol - A type that implements this protocol will have a value in the

PyMappingMethods *tp_as_mapping. This value enables such type to be treated like Python dictionaries using the dictionary syntax for setting and accessing key-value mappings. - Iterator protocol - A type that implements this protocol will have a value in the

getiterfunc tp_iterand possibly theiternextfunc tp_iternextfields enabling instances of the type to be used like Python iterators. - Buffer protocol - A type implementing this protocol will have a value in the

PyBufferProcs *tp_as_bufferfield. These functions will enable access to the instances of the type as input/output buffers.

Next, we look at a few type objects as case studies of how the type object fields are populated.

4.3 Type Object Case Studies

The tuple type

We look at the tuple type to get a feel for how the fields of a type object are populated. We choose this because it is relatively easy to grok given the small size of the implementation - roughly a thousand

plus lines of C including documentation strings. Listing 4.3 shows the implementation of the tuple type.

1 PyTypeObject PyTuple_Type = {

2 PyVarObject_HEAD_INIT(&PyType_Type, 0)

3 "tuple",

4 sizeof(PyTupleObject) - sizeof(PyObject *),

5 sizeof(PyObject *),

6 (destructor)tupledealloc, /* tp_dealloc */

7 0, /* tp_print */

8 0, /* tp_getattr */

9 0, /* tp_setattr */

10 0, /* tp_reserved */

11 (reprfunc)tuplerepr, /* tp_repr */

12 0, /* tp_as_number */

13 &tuple_as_sequence, /* tp_as_sequence */

14 &tuple_as_mapping, /* tp_as_mapping */

15 (hashfunc)tuplehash, /* tp_hash */

16 0, /* tp_call */

17 0, /* tp_str */

18 PyObject_GenericGetAttr, /* tp_getattro */

19 0, /* tp_setattro */

20 0, /* tp_as_buffer */

21 Py_TPFLAGS_DEFAULT | Py_TPFLAGS_HAVE_GC |

22 Py_TPFLAGS_BASETYPE | Py_TPFLAGS_TUPLE_SUBCLASS, /* tp_flags */

23 tuple_doc, /* tp_doc */

24 (traverseproc)tupletraverse, /* tp_traverse */

25 0, /* tp_clear */

26 tuplerichcompare, /* tp_richcompare */

27 0, /* tp_weaklistoffset */

28 tuple_iter, /* tp_iter */

29 0, /* tp_iternext */

30 tuple_methods, /* tp_methods */

31 0, /* tp_members */

32 0, /* tp_getset */

33 0, /* tp_base */

34 0, /* tp_dict */

35 0, /* tp_descr_get */

36 0, /* tp_descr_set */

37 0, /* tp_dictoffset */

38 0, /* tp_init */

39 0, /* tp_alloc */

40 tuple_new, /* tp_new */

41 PyObject_GC_Del, /* tp_free */

42 };

We look at the fields that are populated in this type.

-

PyObject_VAR_HEADhas been initialized with a type object - PyType_Type as the type. Recall that the type of a type object is Type. A look at the PyType_Type type object shows that the type of PyType_Type is itself. -

tp_nameis initialized to the name of the type - tuple. -

tp_basicsizeandtp_itemsizerefer to the size of the tuple object and items contained in the tuple object, and this is filled in accordingly. -

tupledeallocis a memory management function that handles the deallocation of memory when a tuple object is destroyed. -

tuplerepris the function invoked when thereprfunction is called with a tuple instance as an argument. -

tuple_as_sequenceis the set of sequence methods that the tuple implements. Recall that a tuple supportin,lenetc. sequence methods. -

tuple_as_mappingis the set of mapping methods supported by a tuple - in this case, the keys are integer indexes only. -

tuplehashis the function that is invoked whenever the hash of a tuple object is required. This comes into play when tuples are used as dictionary keys or in sets. -

PyObject_GenericGetAttris the generic function invoked when referencing attributes of a tuple object. We look at attribute referencing in subsequent sections. -

tuple_docis the documentation string for a tuple object. -

tupletraverseis the traversal function for garbage collection of a tuple object. This function is used by the garbage collector to help in the detection of reference cycle1. -

tuple_iteris a method that gets invoked when theiterfunction is called on a tuple object. In this case, a completely differenttuple_iteratortype is returned so there is no implementation for thetp_iternextmethod. -

tuple_methodsare the actual methods of a tuple type. -

tuple_newis the function invoked to create new instances of tuple type. -

PyObject_GC_Delis another field that references a memory management function.

The additional fields with 0 values are empty because tuples do not require those functionalities. Take the tp_init field, for example, a tuple is an immutable type, so once created it cannot be changed, so there is no need for any initialization beyond what happens in the function

referenced by tp_new; hence this field is left empty.

The type type

The other type we look at is the type type. This is the metatype for all built-in types and vanilla user-defined types (a user can define a new metatype) - notice how this type is used when initializing the tuple object in PyVarObject_HEAD_INIT. When discussing types, it is essential to distinguish between objects that have type as their type and objects with a user-defined type. This distinction comes very much to the fore when dealing with attribute referencing in objects.

This type defines methods used when working with other types, and the fields are similar to those from the previous section. When creating new types, as we will see in subsequent sections, this type is used.

The object type

Another necessary type is the object type; this is very similar to the type type. The object type

is the root type for all user-defined types and provides some default values that fill in

the type fields of a user-defined type. This is because user-defined types behave differently compared to types that have type as their type. As we will see in subsequent

section, functions such as that for the attribute resolution algorithm provided by the object type differ

significantly from those offered by the type type.

4.4 Minting type instances

With an assumed firm understanding of the rudiments of types, we can progress onto one of the most

fundamental functions of types, which is the creation of new instances.

To fully understand the process of creating new type instances, it is important to remember that just as we differentiate between built-in types and user-defined types 2, the internal structure

of both differs. The tp_new field is the cookie cutter for new type instances in

Python. The

documentation

for the tp_new slot as reproduced below gives a brilliant description of the function that should fill this slot.

An optional pointer to an instance creation function. If this function is NULL for a particular type, that type cannot be called to create new instances; presumably, there is some other way to create instances, like a factory function. The function signature is

PyObject *tp_new(PyTypeObject *subtype, PyObject *args, PyObject *kwds)

The subtype argument is the type of the object being created; the

argsandkwdsarguments are the positional and keyword arguments of the call to the type. Note that subtype doesn’t have to equal the type whose tp_new function is called; it may be a subtype of that type (but not an unrelated type). Thetp_newfunction should callsubtype->tp_alloc(subtype, nitems)to allocate space for the object, and then do only as much further initialization as is absolutely necessary. Initialization that can safely be ignored or repeated should be placed in thetp_inithandler. A good rule of thumb is that for immutable types, all initialization should take place intp_new, while for mutable types, most initialization should be deferred totp_init.

This field is inherited by subtypes but not by static types whose

tp_baseisNULLor&PyBaseObject_Type.

We will use the tuple type from the previous section as an example

of a builtin type. The tp_new field of the tuple type references the - tuple_new method shown in

Listing 4.4, which handles the creation of new tuple objects. A new tuple object is created by dereferencing and then invoking this function.

1 static PyObject * tuple_new(PyTypeObject *type, PyObject *args,

2 PyObject *kwds){

3 PyObject *arg = NULL;

4 static char *kwlist[] = {"sequence", 0};

5

6 if (type != &PyTuple_Type)

7 return tuple_subtype_new(type, args, kwds);

8 if (!PyArg_ParseTupleAndKeywords(args, kwds, "|O:tuple", kwlist, &arg))

9 return NULL;

10

11 if (arg == NULL)

12 return PyTuple_New(0);

13 else

14 return PySequence_Tuple(arg);

15 }

Ignoring the first and second conditions for creating a tuple in Listing 4.4, we follow the third

condition, if (arg==NULL) return PyTuple_New(0) down the rabbit hole to find out how this works.

Overlooking the

optimizations abound in the PyTuple_New function, the segment of the function that creates a new tuple object is the

op = PyObject_GC_NewVar(PyTupleObject, &PyTuple_Type, size) call which allocates memory

for an instance of the PyTuple_Object structure on the heap. This is where a difference between internal

representation of built-in types and user-defined types comes to the fore - instances of built-ins

like tuple are actually C structures. So what does this C struct backing a tuple object look like? It is found in the Include/tupleobject.h as the PyTupleObject typedef, and this is shown in Listing 4.5 for convenience.

1 typedef struct {

2 PyObject_VAR_HEAD

3 PyObject *ob_item[1];

4

5 /* ob_item contains space for 'ob_size' elements.

6 * Items must typically not be NULL, except during construction when

7 * the tuple is not yet visible outside the function that builds it.

8 */

9 } PyTupleObject;

The PyTupleObject is defined as a struct having a PyObject_VAR_HEAD and an array of PyObject

pointers - ob_items. This leads to a very efficient implementation as opposed to representing the instance using Python data structures.

Recall that an object is a collection of methods and data. The PyTupleObject in this case provides

space to hold the actual data that each tuple object contains so we can have multiple instances of

PyTupleObject allocated on the heap but these will all reference the single PyTuple_Type type

that provides the methods that can operate on this data.

Now consider a user-defined class such as in LIsting 4.6.

1 class Test:

2 pass

The Test type, as you would expect, is an object of instance Type. To create an instance of the Test

type, the Test type is called as such - Test(). As always, we can go down the rabbit hole to convince

ourselves of what happens when the type object is called. The Type type has a function reference - type_call that fills the tp_call field, and this is dereferenced whenever the call notation is used on an instance of Type. A snippet of the

type_call

the function implementation is shown in listing 4.7.

1 ...

2 obj = type->tp_new(type, args, kwds);

3 obj = _Py_CheckFunctionResult((PyObject*)type, obj, NULL);

4 if (obj == NULL)

5 return NULL;

6

7 /* Ugly exception: when the call was type(something),

8 don't call tp_init on the result. */

9 if (type == &PyType_Type &&

10 PyTuple_Check(args) && PyTuple_GET_SIZE(args) == 1 &&

11 (kwds == NULL ||

12 (PyDict_Check(kwds) && PyDict_Size(kwds) == 0)))

13 return obj;

14

15 /* If the returned object is not an instance of type,

16 it won't be initialized. */

17 if (!PyType_IsSubtype(Py_TYPE(obj), type))

18 return obj;

19

20 type = Py_TYPE(obj);

21 if (type->tp_init != NULL) {

22 int res = type->tp_init(obj, args, kwds);

23 if (res < 0) {

24 assert(PyErr_Occurred());

25 Py_DECREF(obj);

26 obj = NULL;

27 }

28 else {

29 assert(!PyErr_Occurred());

30 }

31 }

32 return obj;

In Listing 4.7, we see that when a Type object instance is called, the function referenced by the tp_new field is invoked to create a new instance of that type. The tp_init function is also called if it exists to initialize the new instance. This process explains builtin types because, after all, they have their own tp_new and tp_init functions defined already, but what about user-defined types? Most times, a user does not define a __new__ function for a new type (when defined, this will go into the

tp_new field during class creation). The answer to this also lies with the type_new function that fills the tp_new field of the Type.

When creating a user-defined type, such as Test, the type_new function checks for

the presence of base types (supertypes/classes) and when there are none, the PyBaseObject_Type

type is added as a default base type, as shown in listing 4.8.

PyBaseObject_Type is added to list of bases...

if (nbases == 0) {

bases = PyTuple_Pack(1, &PyBaseObject_Type);

if (bases == NULL)

goto error;

nbases = 1;

}

...

This default base type defined in the Objects/typeobject.c module contains some default

values for the various fields. Among these defaults are values for the tp_new and tp_init fields.

These are the values that get called by the interpreter for a user-defined type. In the case where

the user-defined type implements its methods such as __init__, __new__ etc., these values are

called rather than those of the PyBaseObject_Type type.

One may notice that we have not mentioned any object structures like the tuple object structure,

tupleobject, and ask - if no object structures are defined for a user-defined class, how are

object instances handled and where do objects attributes that do not map to slots in the type reside?

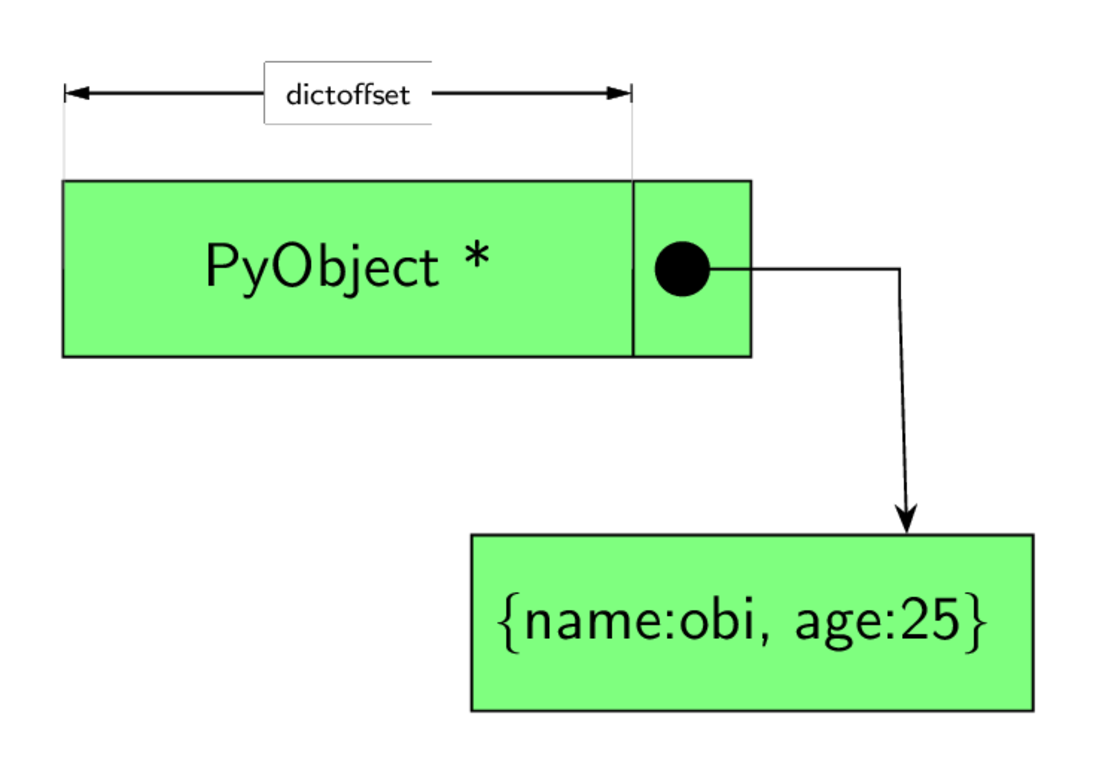

This has to do with the tp_dictoffset field - a numeric field in type object. Instances

are created as PyObjects, however, when this offset value is non-zero in the instance type,

it specifies the offset of the

instance attribute dictionary from the instance (the PyObject) itself as shown in figure 4.0 so for

an instance of a Person type, the attribute dictionary can be assessed by adding this offset value

to the origin of the PyObject memory location.

For example, if an instance PyObject is at 0x10 and the offset is 16 then the instance dictionary

that contains instance attributes is found at 0x10 + 16.

This is not the only way instances store their attributes, as we will see in the following section.

4.5 Objects and their attributes

Types and their attributes (variables and methods) are central to object-oriented programming.

Conventionally, types and instances store their attributes using a dict data structure, but this is not the full story in cases of instances that have the __slots__ attribute defined. This dict data structure resides in one of two places, depending on the type of the object, as was mentioned in the previous section.

- For objects with a type of

Type, thetp_dictslot of type structure is a pointer to adictthat contains values, variables, and methods for that type. In the more conventional sense, we say thetp_dictfield of the type object data structure is a pointer to thetypeorclassdict. - For objects with user-defined types, that

dictdata structure when present is located just after thePyObjectstructure that represents the object. Thetp_dictoffsetvalue of the type of the object gives the offset from the start of an object to this instancedictcontains the instance attributes.

Performing a simple dictionary access to obtain attributes looks simpler than it actually is. Infact,

searching for attributes is way more involved than just checking tp_dict value for instance of

Type or the dict at tp_dictoffset for instances of user-defined types. To get a full understanding, we have to discuss the descriptor protocol - a protocol at the heart of attribute referencing in Python.

The Descriptor HowTo Guide is an excellent

introduction to descriptors, but the following section provides a cursory description of descriptors.

Simply put, a descriptor is an object that implements the

__get__, __set__ or __delete__ special methods of the descriptor protocol. Listing 4.9 is the signature for each of these methods in Python.

descr.__get__(self, obj, type=None) --> value

descr.__set__(self, obj, value) --> None

descr.__delete__(self, obj) --> None

Objects implementing only the __get__ method are non-data descriptors so they can only be read from

after initialization. In contrast, objects implementing the __get__ and __set__ are data descriptors meaning that such descriptor objects are writeable. We are interested in the application of descriptors to object attribute representation. The TypedAttribute descriptor in listing 4.10 is an example of a descriptor used to represent an object attribute.

class TypedAttribute:

def __init__(self, name, type, default=None):

self.name = "_" + name

self.type = type

self.default = default if default else type()

def __get__(self, instance, cls):

return getattr(instance, self.name, self.default)

def __set__(self,instance,value):

if not isinstance(value,self.type):

raise TypeError("Must be a %s" % self.type)

setattr(instance,self.name,value)

def __delete__(self,instance):

raise AttributeError("Can't delete attribute")

The TypedAttribute descriptor class enforces rudimentary type checking for any class’ attribute that it represents. It is important to note that descriptors are useful in this kind of case only when defined at the class level rather than instance-level, i.e., in __init__ method, as shown in listing 4.11.

class Account:

name = TypedAttribute("name",str)

balance = TypedAttribute("balance",int, 42)

def name_balance_str(self):

return str(self.name) + str(self.balance)

>> acct = Account()

>> acct.name = "obi"

>> acct.balance = 1234

>> acct.balance

1234

>> acct.name

obi

# trying to assign a string to number fails

>> acct.balance = '1234'

TypeError: Must be a <type 'int'>

If one thinks carefully about it, it only makes sense for this kind of descriptor to be defined at the type level because if defined at the instance the level, then any assignment to the attribute will overwrite the descriptor.

A review of the Python VM source code shows the importance of descriptors. Descriptors provide the mechanism behind properties,

static methods, class methods, and a host of other functionality in Python. Listing 4.12, the algorithm for resolving an attribute from an instance,b, of a user-defined type, is a concrete illustration of the importance of descriptors.

The algorithm in Listing 4.12 shows that during attribute referencing we first check for descriptor objects;

it also illustrates how the TypedAttribute descriptor can represent an attribute of an

object - whenever an attribute is referenced such as b.name the VM searches the Account

type object for the attribute, and in this case, it finds a TypedAttribute descriptor; the VM then calls __get__ method of the descriptor accordingly. The TypedAttribute example illustrates a descriptor

but is somewhat contrived; to get a real touch of how important descriptors are to the core of the

language, we consider some examples that show how they are applied.

Do note that the attribute reference algorithm in listing 4.12 differs from the algorithm used when referencing an attribute whose type is type. Listing 4.3 shows the algorithm for such.

Examples of Attribute Referencing with Descriptors inside the VM

Consider the type data structure

discussed earlier in this chapter. The tp_descr_get and tp_descr_set fields in a type data structure can be filled in by any type instance to satisfy the descriptor protocol. A function object

is a perfect place to show how this works.

Given the type definition, Account from listing

4.11, consider what happens when we reference the method, name_balance_str, from the class as

such - Account.name_balance_str and when we reference the same method from an instance as shown in listing 4.14.

<bound method Account.name_balance_str of <__main__.Account object at

0x102a0ae10>>

>> Account.name_balance_str

<function Account.name_balance_str at 0x102a2b840>

Looking at the snippet from listing 4.14, although we seem to reference the same attribute, the actual objects returned are different in value and type. When referenced from the account type, the returned value is a function type, but when referenced from an instance of the account type, the result is a bound method type. This is possible because functions are descriptors too. Listing 4.15 is the definition of a function object type.

&PyType_Type, 0)

"function",

sizeof(PyFunctionObject),

0,

(destructor)func_dealloc, /* tp_dealloc */

0, /* tp_print */

0, /* tp_getattr */

0, /* tp_setattr */

0, /* tp_reserved */

(reprfunc)func_repr, /* tp_repr */

0, /* tp_as_number */

0, /* tp_as_sequence */

0, /* tp_as_mapping */

0, /* tp_hash */

function_call, /* tp_call */

0, /* tp_str */

0, /* tp_getattro */

0, /* tp_setattro */

0, /* tp_as_buffer */

Py_TPFLAGS_DEFAULT | Py_TPFLAGS_HAVE_GC,/* tp_flags */

func_doc, /* tp_doc */

(traverseproc)func_traverse, /* tp_traverse */

0, /* tp_clear */

0, /* tp_richcompare */

offsetof(PyFunctionObject, func_weakreflist), /* tp_weaklistoffset */

0, /* tp_iter */

0, /* tp_iternext */

0, /* tp_methods */

func_memberlist, /* tp_members */

func_getsetlist, /* tp_getset */

0, /* tp_base */

0, /* tp_dict */

func_descr_get, /* tp_descr_get */

0, /* tp_descr_set */

offsetof(PyFunctionObject, func_dict), /* tp_dictoffset */

0, /* tp_init */

0, /* tp_alloc */

func_new, /* tp_new */

};

The function object fills in the tp_descr_get field with a func_descr_get function thus instances

of the function type are non-data descriptors.

Listing 4.16 shows the implementation of the funct_descr_get method.

static PyObject * func_descr_get(PyObject *func, PyObject *obj, PyObject *type){

if (obj == Py_None || obj == NULL) {

Py_INCREF(func);

return func;

}

return PyMethod_New(func, obj);

}

The func_descr_get can be invoked during either type attribute resolution or instance attribute resolution, as described in the previous section. When invoked from a type, the call to the func_descr_get

is as such local_get(attribute, (PyObject *)NULL,(PyObject *)type) while when invoked from an attribute

reference of an instance of a user-defined type, the call signature is f(descr, obj, (PyObject *)Py_TYPE(obj)).

Going over the implementation for func_descr_get in listing 4.16, we see that if the instance is NULL, then the function

itself is returned while if an instance is passed in to the call, a new method object is created

using the function and the instance. This sums up how Python can return a different type for the same function reference using a descriptor.

In another instance of the importance of descriptors, consider the snippet in Listing 4.17 which

shows the result of accessing the __dict__ attribute from both an instance of the built-in type

and an instance of a user-defined type.

__dict__ attribute from an instance of the built-in type and an instance of a user-defined typeclass A:

pass

>>> A.__dict__

mappingproxy({'__module__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__weakref__': <attribute '\

__weakref__' of 'A' objects>, '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'A' objects>})

>>> i = A()

>>> i.__dict__

{}

>>> A.__dict__['name'] = 1

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'mappingproxy' object does not support item assignment

>>> i.__dict__['name'] = 2

>>> i.__dict__

{'name': 2}

>>>

Observe from listing 4.17 that both objects do not return the vanilla dictionary type when the

__dict__ attribute is referenced. The type object seems to return an immutable mapping proxy that we cannot even assign. In contrast, the instance of type returns a vanilla dictionary mapping that supports all the usual dictionary functions. So it seems that attribute referencing is done differently for these objects. Recall the algorithm described for attribute search from a couple of sections back.

The first step is to search the __dict__ of the type of the object for the attribute, so we go ahead

and do this for both objects in listing 4.18.

__dict__ in type of objects>>> type(type.__dict__['__dict__']) # type of A is type

<class 'getset_descriptor'>

type(A.__dict__['__dict__'])

<class 'getset_descriptor'>

We see that the __dict__ attribute is represented by data descriptors for both objects, and that is why we can get different object types. We would like to find out what happens under the covers for this descriptor, just as we did in the functions and bound methods. A good

place to start is the Objects/typeobject.c module and the definition for the type type

object. An interesting field is the tp_getset field that contains an array of

C structs (PyGetSetDef values) shown in listing 4.19. This is the collection of values that will be represented by descriptors in type's type __dict__ attribute - the __dict__ attribute is the mapping referred to by the tp_dict slot of the type object points.

__dict__ in type of objectsstatic PyGetSetDef type_getsets[] = {

{"__name__", (getter)type_name, (setter)type_set_name, NULL},

{"__qualname__", (getter)type_qualname, (setter)type_set_qualname, NULL},

{"__bases__", (getter)type_get_bases, (setter)type_set_bases, NULL},

{"__module__", (getter)type_module, (setter)type_set_module, NULL},

{"__abstractmethods__", (getter)type_abstractmethods,

(setter)type_set_abstractmethods, NULL},

{"__dict__", (getter)type_dict, NULL, NULL},

{"__doc__", (getter)type_get_doc, (setter)type_set_doc, NULL},

{"__text_signature__", (getter)type_get_text_signature, NULL, NULL},

{0}

};

These values are not the only ones represented by descriptors in the type dict; there are other values such as

the tp_members and tp_methods values which have descriptors created and insert into the tp_dict

during type initialization. The insertion of these values into the dict happens when the PyType_Ready function is called on the type. As part of the PyType_Ready function initialization process, descriptor objects are created

for each entry in the type_getsets and then added into the tp_dict mapping - the add_getset

function in the Objects/typeobject.c handles this.

Returning to our __dict__, attribute, we know that after initialization of the type, the __dict__

attribute exists in the tp_dict field of the type, so let’s see what the getter function of this descriptor does. The getter function is the type_dict function shown in listing 4.20.

typestatic PyObject * type_dict(PyTypeObject *type, void *context){

if (type->tp_dict == NULL) {

Py_INCREF(Py_None);

return Py_None;

}

return PyDictProxy_New(type->tp_dict);

}

The tp_getattro field points to the function that is the first port of call for getting attributes for any object. For the type object, it points to the type_getattro function. This method, in turn,

implements the attribute search algorithm as described in listing 4.13. The

function invoked by the descriptor found in the type dict for the __dict__ attribute is the

type_dict function given in listing 4.20, and it is pretty easy to understand.

The return value is of interest to us here; it is a dictionary proxy to the actual dictionary that

holds the type attribute; this explains the mappingproxy type that is returned when we query the __dict__ attribute of a type object.

So what about the instance of A, a user-defined type, how is the __dict__ attribute resolved? Now

recall that A is an object of type type so we go hunting in the Object/typeobject.c

module to see how new type instances are created. The tp_new slot of the PyType_Type contains the

type_new function that handles the creation of new type objects. Perusing through all the type creation code in the function, one stumbles on the snippet in listing 4.21.

tp_getset field for user defined typeif (type->tp_weaklistoffset && type->tp_dictoffset)

type->tp_getset = subtype_getsets_full;

else if (type->tp_weaklistoffset && !type->tp_dictoffset)

type->tp_getset = subtype_getsets_weakref_only;

else if (!type->tp_weaklistoffset && type->tp_dictoffset)

type->tp_getset = subtype_getsets_dict_only;

else

type->tp_getset = NULL;

Assuming the first conditional is true as the tp_getset field is filled with the value shown in Listing 4.22.

getset values for instance of typestatic PyGetSetDef subtype_getsets_full[] = {

{"__dict__", subtype_dict, subtype_setdict,

PyDoc_STR("dictionary for instance variables (if defined)")},

{"__weakref__", subtype_getweakref, NULL,

PyDoc_STR("list of weak references to the object (if defined)")},

{0}

};

When (*tp->tp_getattro)(v, name) is invoked, the tp_getattro field which contains a pointer to

the PyObject_GenericGetAttr is called. This function is responsible for

implementing the attribute search algorithm for a user-defined types. In the case of the __dict__

attribute, the descriptor is found in the object type’s dict and the __get__ function of the